Despite our now ubiquitous reliance on the internet, it wasn’t until the nineties that it evolved into an iteration we would recognise today. Activism and campaigning, of course, precede the emergence of the World Wide Web by centuries. Oppressed people have always fought against their oppressors, making the practice of activism a historic reality as foundational as the invention of the internet itself. The struggle for equality and liberation has always been driven by Black and Indigenous People, colonised people, people of colour, women, LGBTQIA+ people, disabled people, working class people, those living in poverty and people from marginalised religions.

Climate justice activism is no exception – these same communities are affected first and worst by both the causes and the consequences of the climate crisis. The lives of marginalised people are considered of little to no value by those seeking to profit from oil pipelines and other extractivist ventures: communities are killed and displaced, their land destroyed. Geopolitical inequities mean that marginalised people are also disproportionately impacted by the pollution, natural disasters and famine induced by such carbon-intensive, exploitative processes. In the UK, for example, data shows that air pollution is highest in areas with mixed or multiple ethnic groups compared to white, wealthier areas.

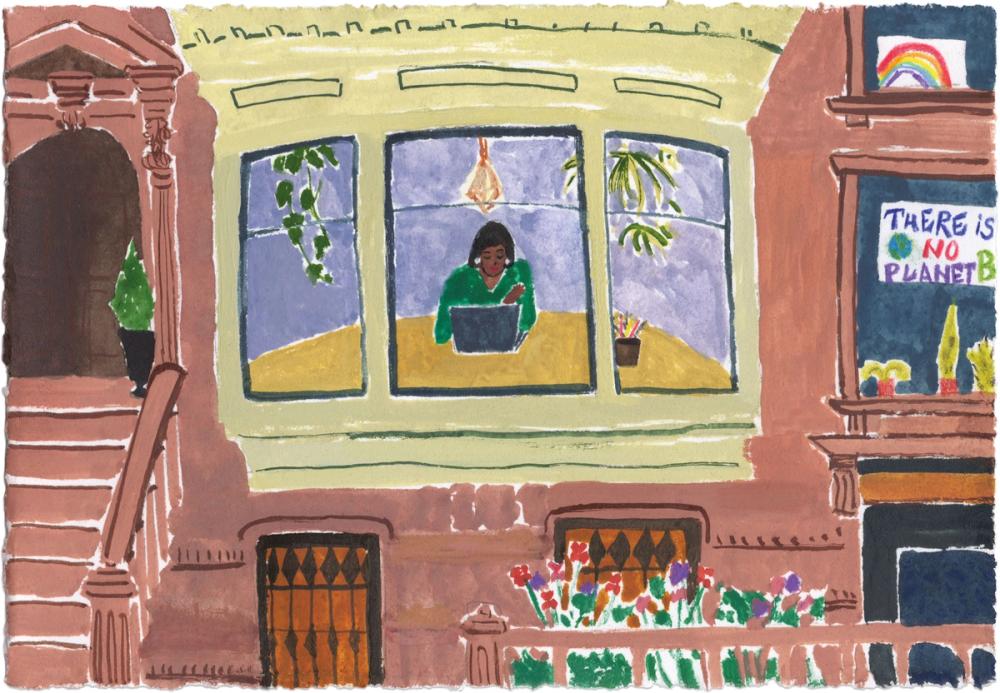

As technology has given us new and easier ways to share information, activism and organising have rapidly moved online. Almost in parallel, the green movement has gone from fringe to mainstream: the majority of people consider climate change a global emergency, including 81% of the UK population. The online world is a platform for education, enabling those on the frontlines of the climate crisis to share their experiences globally. It has provided tools to help campaigners mobilise, organise, and communicate with each other regardless of location, time zone, and language. For those who are unable to participate in-person, whether due to disability, neurodivergency, mental health issues, or socio-economic reasons, technology enables accessible and inclusive participation in social change. Disability visibility movement #CripTheVote has for many years held a powerful online presence, amplifying the voices of disabled people.

Disability visibility movement #CripTheVote has for many years held a powerful online presence, amplifying the voices of disabled people

However, the internet is not without its dark side: anonymity fuels online abuse and facilitates pathways to extremism; inability to access internet leads to further exclusion of already-marginalised people; algorithms create echo chambers; capitalism capitalises on allyship; and mass surveillance threatens livelihoods. As the planet heats up exponentially, questions arise with regards to how we might circumnavigate these problems and create effective change.

What works?

In 2020, the pandemic wasn’t the only event labelled as ‘unprecedented’: we also saw a spike in social media usage, online activism and anti-racism protest. ‘Unprecedented’ may be a little generous: these same platforms have been credited with sparking the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street movements of the 2010s. However, lockdowns that pushed more of the world online than ever before catalysed frenzied discussions on issues of social and racial injustice while those experiencing them directly had the world’s attention. For the climate movement, which in the Global North is predominantly made up of white people, this was a much-needed reminder of the need for inclusive, unified organising. Black Lives Matter is a movement, but it’s also an ideology which promotes the duplicitously simple-yet-complex notion of racial equality across all areas of life. This includes the climate movement, whose members must adopt anti-racism as a founding principle and place a greater focus on how race and the climate crisis intersect.

Lockdowns pushed more of the world online than ever before catalysed frenzied discussions on issues of social and racial injustice

The terms ‘performative activism’ and ‘slacktivism’ were heavily circulated during and following the events of 2020, referring to aesthetic or lazy shows of solidarity lacking any real, tangible action. Shortly after George Floyd’s murder, Instagram was flooded with educational resources about systemic racism. For many it was the first time they had engaged with the insidiousness of global anti-Blackness. Then, one day, people suddenly started posting a single, plain black square to their grid instead. Misinterpreted as a Black-led campaign, ‘Blackout Tuesday’ ended up as a shallow attempt to show support for Black Lives Matter. Appearing in their tens of millions, the mass of black squares took over Instagram’s algorithms, burying the useful, informative posts. Many people posted a square without sharing any other resources or helpful information before, after or since.

This overly simplified ability to express performative support still plagues Maja Antoine-Onikoyi, a poet and founder of Maja’s Education Project, an anti-racist book distribution service. ‘It was,’ she summarises, ‘the most useless thing that came out of 2020, and that’s saying something.’ Around this time, fair fashion campaigner and influencer Venetia La Manna dropped the label ‘activist’ from her Instagram bio, citing its erroneous and problematic glamourisation. She particularly criticised the way companies co-opted the word and theme of activism in their advertising and products to turn profit: ‘it was being hijacked to undermine the very purpose of activism and the hard work of organisers who are fighting for liberation outside of this current oppressive system.’ These trends are not just frustrating, but also have the potential to hinder progress.

Fair fashion campaigner and influencer Venetia La Manna dropped the label ‘activist’ from her Instagram bio, citing its erroneous and problematic glamourisation

Writing for Digital Trends, journalist Talia Lavin explains that ‘disability activism has existed online for years and decades – it serves as both a supplement to on-the-ground actions and a means for connection, to each other as well as to politicians and the general public.’ Activists don’t take issue with those who cannot participate in person – it’s the people, celebrities and brands who can participate, but choose not to, or whose engagement is shallow and meaningless, that have become focal points of criticism. Daze Aghaji, a climate justice activist who previously volunteered with Extinction Rebellion (XR), is clear about the distinction: ‘If I don’t see you do something in real life, I don’t care what you’re doing online, I don’t see it as activism.’

Her sentiment reflects ongoing discussions within the climate justice movement about strategies for substantive change. Although studies show that online activism does influence offline action, often by inspiring others to take part, the value of both digital and real-life action lack singular definition.

As the clock ticks and those in power obstinately refuse to respond accordingly to the crisis, many campaigners believe that traditional tactics – whether petitions and social media campaigns or established forms of street protest – neither match the scale of the problem, nor tackle its root causes. ‘Social media is all too convenient a tool that simplifies the reality of social change, but transformation requires more than relationships of convenience,’ says Tamsin Omond, one of the founding members of Extinction Rebellion and veteran climate activist. XR’s theory of change is based on building a mass movement of people willing to commit civil disobedience in a bid to force the government to take appropriate action. Omond believes that in-person talks and people attending XR’s actions did more to push the climate agenda than Instagram could have done. Danielle Sams, a climate and social justice activist based in Germany, agrees: ‘As climate activists, we know we need radical system change for the world not to burn and flood,’ she says. It is clear that this will not come from shallow social media engagement in complex issues. Aghaji believes progress is also hindered by online echo chambers: ‘The world is so polarised right now as we’re never questioned about our own beliefs. If you don’t like what someone says [online], you can just unfollow and block them.’

Mobilising, organising, and activism are not interchangeable terms: mobilising inspires people to want to take action, organising involves arranging the logistics of that action, and activism is what that action looks like. Social media has quite rapidly become the most effective and widespread way to educate people on systemic issues like the climate emergency and encourage a strong desire to do something about it. Organising feels almost impossible without technology more widely – phones, secure communication, instant messaging. It’s activism itself, the shape the action takes, that presents a more complex dilemma. Many activists pushing for systemic change feel that social media makes it too easy to make activism look easy, and too difficult to portray the full extent of its challenges.

Without it, however, we may not have seen anything close to the scale of the Black Lives Matter protests that occurred in the summer of 2020, nor would Extinction Rebellion have succeeded in bringing major cities across the world to a standstill in 2019 with their two-week mass civil disobedience blockade. As we slowly begin to return to the streets post-lockdown, this seems like an important opportunity for the climate movement to reflect on the slacktivism of the past year and improve on the ways in which we meaningfully connect online and offline action.

Digital security and activist surveillance

In 2013, Edward Snowden, a CIA employee, exposed global mass surveillance programmes run by the US and other governments. This relatively recent revelation uncovered a new realm of threat to the work of activists, journalists and human rights defenders across the world.

Almost all struggles for social justice contend with intersecting elements of our social, economic, cultural, political and racial systems. These are created, defined and upheld by oppressive hierarchies based on characteristics such as class, race, gender and sexuality. Power is concentrated at the top, led by governments and bolstered by the institutions they control like the police, the military and intelligence services. Added into the mix is the power big corporations wield over all arms of the state, through lobbying and the intrinsic privatisation of our entire economy. Holding onto this concentrated power and profit relies on maintaining hierarchies and inequalities – dominant powers need oppressed groups to stay oppressed so they can stay dominant.

Added into the mix is the power big corporations wield over all arms of the state, through lobbying and the intrinsic privatisation

Activism jeopardises this, and the state has no qualms in leveraging its position to surveil and target anyone they deem a threat. In 2020, and not for the first time, animal rights and environmental campaign groups were placed on a list of ‘extremist’ organisations by the London Metropolitan Police. Amongst these were Greenpeace, Extinction Rebellion and youth climate strikers. In specific response to XR’s place on the list, the Met pointed to its ‘anti-establishment philosophy that seeks system change.’ Though the list was rescinded shortly after its release, it exposed the troubling truth about the state’s view of those engaging in peaceful, non-violent protest.

The popularity of social media and widespread ignorance about the dangers and scope of surveillance make it easy for police to identify protesters through both public and private channels. Micah Lee was the first person Edward Snowden successfully contacted when he decided to blow the whistle. Lee, currently the Director of Information Security at First Look Media, forgives these shortcomings: ‘You can’t really blame people for having bad security practices when this is just how everything is set up and it’s all they ever know.’ Alexandra, Programme Officer at Digital Defenders Partnership (DDP), reinforces this: ‘We are the first generation in human history which has to use, intensively, technologies that track or surveil us. Our education systems aren’t prepared to properly educate or train us to understand... the technologies that we use.’

‘We are the first generation in human history which has to use, intensively, technologies that track or surveil us'

It is possible to mitigate the risks – some hackers have got away with total anonymity – but doing so is not without its challenges. End-to-end encryption is considered the safest way for activists to communicate since it prevents messages being read by anyone except the intended recipients. The use of encrypted apps has grown considerably since Snowden’s leaks, though not everyone is a fan. ‘The FBI has, for a long time, been trying to outlaw end-to-end encryption,’ Lee explains. The intelligence-gathering organisation refers to the ‘going dark problem’, their alleged struggle to catch terrorists who are taking advantage of encrypted communication. This is, Lee says, entirely untrue: the FBI simply has to innovate its techniques, but this fear-filled narrative is now seeping into mainstream conversation. Both Lee and Rory Byrne, the Managing Director of digital safety firm Security First, predict that ‘unnecessary pushes towards weakening or damaging encryption’ present one of the greatest threats to the future of online security.

Byrne also points out the specific dangers frontline environmental campaigners come up against. Often campaigning as lone individuals or in small groups, they lack the formal support structure of an NGO or traditional social movement. Even then, the hardware and software that would provide better protection is often inaccessible and too expensive. This often leaves activists to contend with surveillance states unprotected, rendering them vulnerable to infiltration from both the police, and reactionary journalists. Before technology made surveillance easier, the police already infiltrated environmentalist groups and the lives of its members. In instances such as the ‘spy cops scandal’, the police have revealed to have even had long-term relationships and, in some cases, children, with climate activists.

Alexandra of the DDP also notes that ‘surveillance technologies always have a more severe impact on marginalised populations, such as women, racial or ethnic minorities, and rural and Indigenous communities.’ Wretched of the Earth, a grassroots climate justice movement led by and for people from marginalised communities, expressed this lived reality in a statement addressed to XR in 2019:

‘Many of us live with the risk of arrest and criminalization. We have to carefully weigh the costs that can be inflicted on us and our communities by a state that is driven to target those who are racialised ahead of those who are white.’

The problem feeds the result: there is an inevitable connection between the dominance of white, middle class campaigners in the Global North’s environmental movement with the misfocus on simplistic strategies that fail to adequately tackle the climate crisis.

Battling time

It is now almost impossible to imagine how a protest message or movement could reach a critical mass without the internet. For activists, the dangers are vast, disproportionately so for people from marginalised communities. Alexandra of the DDP points out that, alongside physical and material threats such as online harassment, surveillance ‘can lead to greatly detrimental outcomes on the mental and physical wellbeing of individuals and groups.’ The very system climate justice activists work to dismantle is the movement’s greatest threat. The state will use every tool at its disposal to crush and inspire hopelessness in those fighting against it.

The state will use every tool at its disposal to crush and inspire hopelessness in those fighting against it

However, we have neither the time nor the luxury to concede this fight: environmental catastrophe is already a reality for much of the world. Now, our focus must be on reducing its impact wherever possible. The need to avoid 1.5 oC of global warming presents a systemic dilemma of classism, capitalism, racism and oppression, as far reaching as the possibilities of the online world. Harnessing the digital tools available to galvanise support and technology which protects, but can also expose, must become a key focus of the climate justice movement. For those seeking hope, it may be found in knowing that this is well within reach.

Tim Williamson, Rosie Brook, Richard German, Justine Raoult, Air Pollution Exposure in London, 2019.

UNDP and the University of Oxford, The Peoples' Climate Vote, 2021.

Kalhan Rosenblatt, A Summer of Digital Protest, 2020.

Talia Lavin, Keyboard warriors: How the Internet can be a Lifeline for Disabled Activists, 2020.

Hedy Greijdanus et al., The Psychology of Online Activism and Social Movements, 2020, & Ning Wang et al., The Critical Periphery in the Growth of Social Protests, 2020.

See Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of structural intersectionality in Mapping the Margins, 1991.

More Reads

Technology

Memory Loss and the Metaverse

Keep readingFrom gaming to virtual museum tours to Google Earth, the use of interactive digital spaces to record places, store information and build online worlds is well-established. But the metaverse is now recording real spaces and vanishing places. Nicholas Pritchard examines what museums and photographic records do to our sense of the world – and questions whether commercial cloud spaces are the right next step for our cultural and ecological memories.

By Nicholas PritchardKeep readingThe matter that makes us will be here long after we are gone, but what kind of mark will we leave? In this IFLA! classic, from our Regeneration Issue, Phoebe Thomson explores deathscapes – 'landscapes of death' – and the legacies our bodies leave behind, from British cemeteries to Parsi Towers of Silence. She wonders whether a regenerative approach to handling death can breathe new life into old spaces. Illustrated by our very own Matthew Lewis.

Keep reading >

Landscapes

Death, Landscape, and the Environment

By Phoebe Thomson(Article)Landscapes

Death, Landscape, and the Environment

Keep readingThe matter that makes us will be here long after we are gone, but what kind of mark will we leave? In this IFLA! classic, from our Regeneration Issue, Phoebe Thomson explores deathscapes – 'landscapes of death' – and the legacies our bodies leave behind, from British cemeteries to Parsi Towers of Silence. She wonders whether a regenerative approach to handling death can breathe new life into old spaces. Illustrated by our very own Matthew Lewis.

By Phoebe ThomsonKeep readingArchitecture

A Call for Ancestral Futurism: decolonizing and decarbonizing architecture

Keep readingIn Jamaica, the ‘Isle of Wood and Water’, locals find themselves caught between traditional and modernist values, especially when it comes to building new homes. Teshome Douglas-Campbell explores this phenomenon through the lens of ‘Ancestral Futurism’, finding a new way forward that takes inspiration from architects and architecture from across the global South.

By Teshome Douglas-CampbellKeep reading- Read more