More Reads

The Real Origins of the Zero Waste Movement

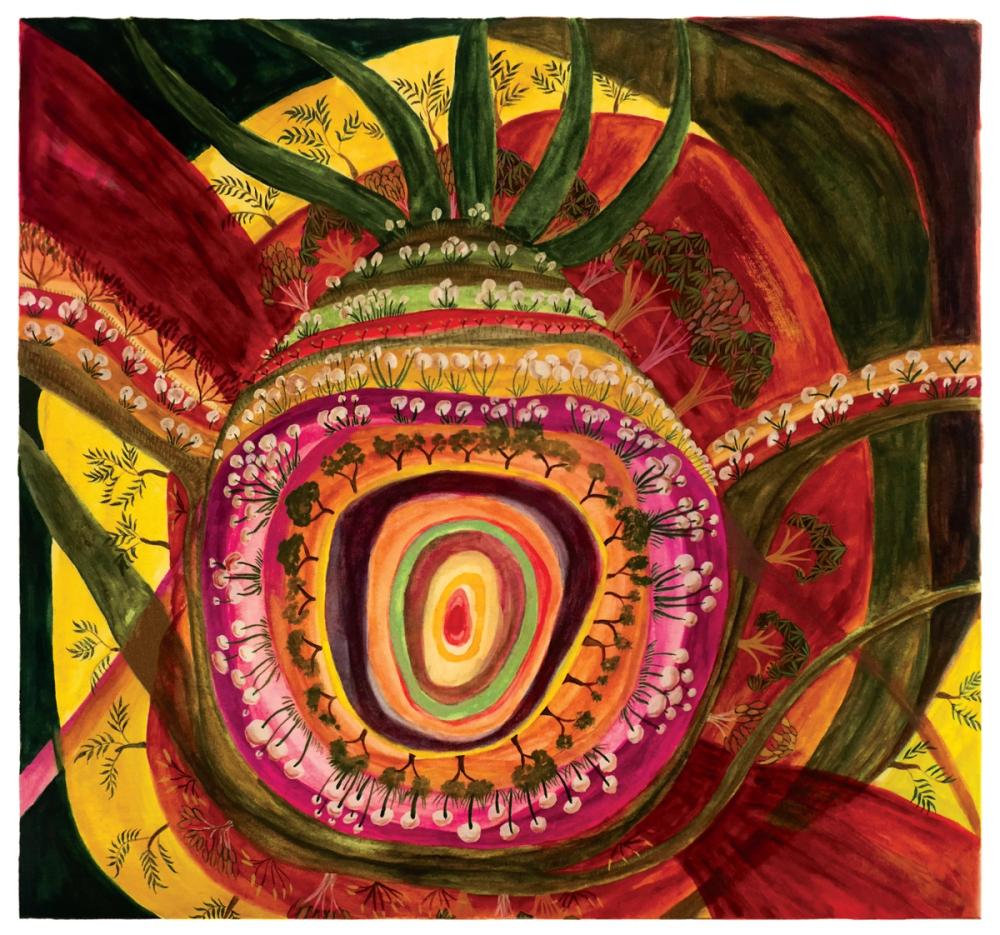

As people reach for their cookbooks during self-isolation, instagram influencers and food trends are seeing a huge influx of interest. Sharlene Gandhi explores the real origins of the zero waste movement, and the whitewashed gentrification that remains prevalent in environmentalist principles around eating. Illustrated by Hannah Percy.

By Sharlene GandhiKeep readingThe Perks and Perils of Online Activism

The last few years have seen a surge in online protest, but how effective has it been? Molly Lipson argues that, while online activism offers an important opportunity for mobilising and organising action, it often fails to add up to action on the ground. With the ever-present threat of infiltration and state-surveillance, activists have to navigate a considerable minefield as they work to harness the potential of online protest. Illustrated by Fan Pu.

By Molly LipsonKeep readingDeath, Landscape, and the Environment

The matter that makes us will be here long after we are gone, but what kind of mark will we leave? In this IFLA! classic, from our Regeneration Issue, Phoebe Thomson explores deathscapes – 'landscapes of death' – and the legacies our bodies leave behind, from British cemeteries to Parsi Towers of Silence. She wonders whether a regenerative approach to handling death can breathe new life into old spaces. Illustrated by our very own Matthew Lewis.

By Phoebe ThomsonKeep reading