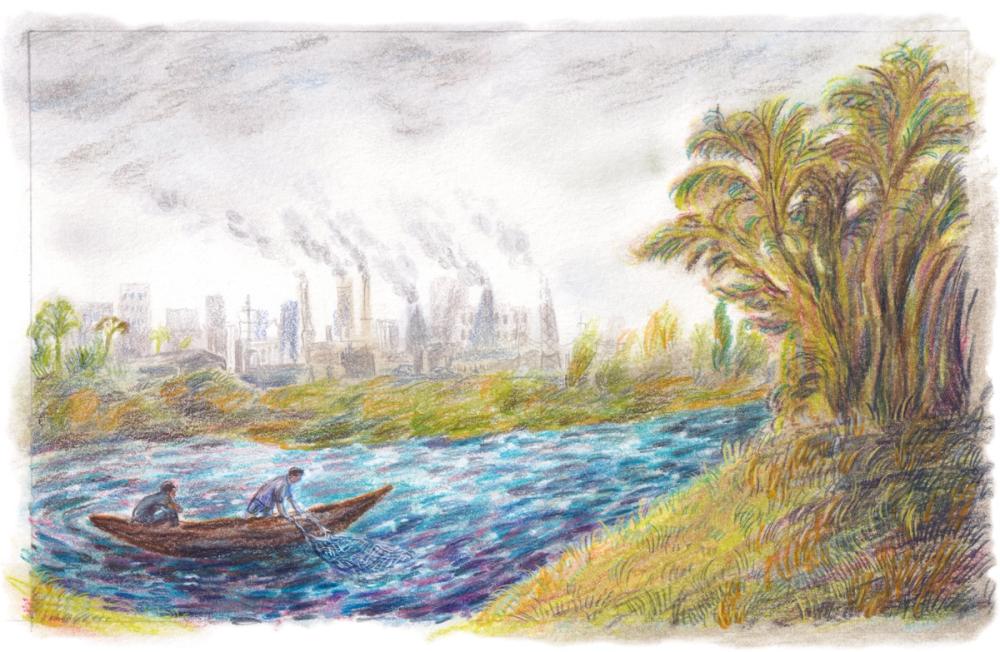

This morning, I put on a sweatshirt made in Vietnam. I purchased an Americano (a ‘complex blend of organic beans from Peru, Honduras, Ethiopia and Sumatra’). Then I sat down to write about climate reparations in a British city built from the proceeds of the transatlantic slave trade. As I write, the Global South (and, increasingly, though in different ways, those marginalised within the Global North) still unwillingly foot the bill of my high-consumption lifestyle. In Britain, the average person emits more carbon in two weeks than the average person in Rwanda, Malawi, Ethiopia, Uganda, Madagascar, Guinea and Burkina Faso combined. Historically, as Britain’s appetite grew, it set in motion processes of colonial extraction that ‘changed local ecosystems and reduced environmental capacity over centuries, while creating a racialised hierarchy among those bearing the climate crisis’ worst effects’.

Yet, on paper (read:according to global law and policy), I owe the Global South nothing. The fact that I stand on the shoulders of violent colonial giants here in Bristol does not saddle me with any legal obligation to atone, or correct.

In fact, on paper, it is the Global South that owes the Global North. Colonial coercion and enforced dependency are today preserved through international financial systems that keep the Global South fiscally indebted to the Global North. Over the last ten years, this has only been exacerbated by extreme climate events, with the external debts of Small Island Developing States rising by 24%, for example. This unjust financial debt is frequently discussed in contrast with an infinitely more significant debt: the ecological debt owed for centuries of coercive resource extraction and ecological devastation, upon which the Global North built its wealth.

The Global North’s balance sheet is at best hopelessly incomplete, and at worst, criminally deceptive. It is time we discarded it in favour of conceptions of debt and reparation that emerge from the knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples and those from the Global South – a diverse group with the common (yet differentiated) experience of living through the ecological devastation wrought by Western colonial capitalism.

Colonial coercion and enforced dependency are today preserved through international financial systems

As Mae Buenaventura from the Asian Peoples Movement on Debt and Development explains: ‘Financial debts being collected from us are miniscule compared with the climate debt and ecological debt owed to the Global South. Climate debt is what we are demanding – not as charity, but as justice – through restitution and reparations.’ Thus Broulaye Bagayoko (Permanent Secretary for the Coalition of Alternative Debt and Development in Mali) says: ‘the first step would be to recognise that the countries considered as ‘indebted’ are in fact the creditors and to correct this particular view of the world. The second step consists in paying reparations for these human, economic, and ecological crimes committed in history’.

In their 2021 report, the IPCC concluded that ‘it is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, oceans and land.’ A crueller, more accurate version of this conclusion was stated in the Universal Declaration for the Rights of Mother Earth drafted at the People’s Conference on the Rights of Mother Earth at Cochabamba, hosted by Bolivian President Evo Morales following disappointing outcomes at COP15: 'the causes of climate change are clear. Developed countries have appropriated the Earth’s atmospheric space by emitting the vast majority of historical greenhouse gas emissions, while they only represent 20% of the world’s population. The way to solve the climate crisis in a fair, effective and scientifically sound way is to honour climate debts.'

There are several policy-based ways in which these debts might be ‘paid’. Open borders for climate migrants – as discussed by Rudy Schulkind in this issue of IFLA! – have been cited as an essential part of a reparative approach to climate justice. Climate litigation (holding companies and nations legally accountable for climate devastation, ideally with compensation for affected communities) is also considered part of a broader reparative strategy.

At the global policy level, several mechanisms have been introduced to facilitate the transfer of ‘climate finance’ from rich countries to so-called developing countries. For instance, the UN’s Green Climate Fund is tasked with providing finances to enhance the ‘adaptation’ and ‘mitigation’ in developing countries (though only a small fraction of the promised amount has actually been committed, and much of this comes from private sector funding and loans rather than cash grants). Distinct from mitigation and adaptation is the notion of ‘loss and damage’, which many regard as most analogous with the idea of direct reparations – that funds should be transferred to compensate nations for historic or ongoing damages. The Warsaw International Mechanism on Loss and Damage was set up at COP19 in 2014 with a mandate to (in theory) manage such compensation and the Mechanism was reaffirmed in Article 8 of the Paris Agreement. Crucially, however, it also contains an important caveat: ‘Article 8... does not involve or provide a basis for any liability or compensation.’ In other words, the Mechanism, despite being one of the most expedient strategic opportunities for direct reparations, has no teeth.

The climate policy narratives of the Global North perpetuate the racial othering that has always defined colonial capitalism, positioning the transfer of knowledge to the Global South at the centre of climate responses – rather than the transfer of cold, hard reparations. This is laughable considering the climate crisis is the product of Western knowledge systems and market-based philosophies that gave rise to the climate crisis in the first place. We might instead, then, look to different Indigenous Peoples' knowledge systems and ways of knowing for new perspectives on appropriate climate responses.

Voices from these spaces have long called for a climate narrative that emphasises restorative justice and repair. Philosophies such as the Bantu conception of ubuntu (‘I am because you are’), the Quechuan notion of sumak kawsay/buen vivir (the experience of good living, and wellbeing in its social context), and the Anishinaabe philosophy of mnaamodzawin (‘living well’ or ‘the good life’), have all made their way into prominent discourses on climate justice in recent years. These philosophies are all rooted in worldviews that foreground the importance of respecting and honouring relationships, based on an understanding of the essential interconnectedness of people (and the embeddedness of humans in nature and ecology). The Declaration of Rights of Nature from the People’s Conference at Cochabamba reflects this, introducing itself with ‘We, the peoples and

nations of Earth: considering that we are all part of Mother Earth, an indivisible, living community of interrelated and interdependent beings with a common destiny...’

The Global North has damaged this shared integrity through generations of mass othering, objectification, and subjugation. It owes a debt in the rigid Western, financial sense, but it is also spiritually, socially, and morally indebted to the Global South. It owes a debt that we cannot fully comprehend with the cognitive tools given to us by Western worldviews.

A focus on relationality and connectedness, rather than the exclusionary logics that currently define state sovereignty and national borders, might encourage us to think of climate reparation as a constellation of commitments and movements with, as Mae Buenaventura says, the collective aim of the ‘profound transformation of the global system and national economies.’

I finish this piece still sitting in a city built from the spoils of colonial extraction. Of course, I bear some responsibility to reflect upon the consequences of my individual actions and minimise ecological harm. However, despite what BP might have us believe, the climate crisis is not merely an individual crisis. In fact, we might think of the climate emergency as a crisis of individuality, which has long obscured collective, communal connections and shared responsibilities. We have a collective duty to push towards a shift in discourse that foregrounds the Global North’s outsized responsibility for the climate crisis. Together, we must together insist that just debts are paid, and cruel ones are cancelled.

Harpreet Kaur Paul, We need climate reparations to confront the colonial past, 2021.

Roxanna Baldrich, Who pays? Debt, Reparations, and Accountability in Perspectives on a Global Green New Deal, ed. by Harpeet Kaur and Dalia Gabriel, 2021.

Leon Sealey-Huggins, 1.5°C to stay alive’: climate change, imperialism and justice for the Caribbean, 2017.

Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, Beba Cibralic, The Case for Climate Reparations, 2020

See Eleanor Leydon’s article on page 39 in this issue of It’s Freezing in LA!

Mark Kaufman, The Carbon Footprint Sham, 2021.

More Reads

Economics

You Can't Put a Price on Nature

Keep readingIn recent years, the marketisation of ‘natural capital’ has made serious inroads in the finance sector. Adrienne Buller asks if so-called green financing can every really account for the dynamism and complexity of the natural world, or whether attempting to put a price on pollution will only fast track ecological decline. Illustrated by Anthony Padilla.

By Adrienne BullerKeep readingTechnology

The Perks and Perils of Online Activism

Keep readingThe last few years have seen a surge in online protest, but how effective has it been? Molly Lipson argues that, while online activism offers an important opportunity for mobilising and organising action, it often fails to add up to action on the ground. With the ever-present threat of infiltration and state-surveillance, activists have to navigate a considerable minefield as they work to harness the potential of online protest. Illustrated by Fan Pu.

By Molly LipsonKeep readingThe matter that makes us will be here long after we are gone, but what kind of mark will we leave? In this IFLA! classic, from our Regeneration Issue, Phoebe Thomson explores deathscapes – 'landscapes of death' – and the legacies our bodies leave behind, from British cemeteries to Parsi Towers of Silence. She wonders whether a regenerative approach to handling death can breathe new life into old spaces. Illustrated by our very own Matthew Lewis.

Keep reading >

Landscapes

Death, Landscape, and the Environment

By Phoebe Thomson(Article)Landscapes

Death, Landscape, and the Environment

Keep readingThe matter that makes us will be here long after we are gone, but what kind of mark will we leave? In this IFLA! classic, from our Regeneration Issue, Phoebe Thomson explores deathscapes – 'landscapes of death' – and the legacies our bodies leave behind, from British cemeteries to Parsi Towers of Silence. She wonders whether a regenerative approach to handling death can breathe new life into old spaces. Illustrated by our very own Matthew Lewis.

By Phoebe ThomsonKeep reading- Read more